December 13, 2022

Meredith Monk's 'The Recordings'- 13-CD Set Documents Four Decades

Tim Pfaff READ TIME: 6 MIN.

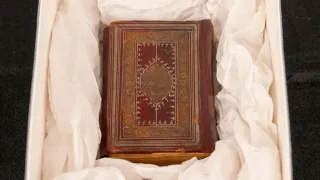

One of the quiet revelations of "Meredith Monk: The Recordings" (ECM New Series) is that Monk herself confides that it was Janis Joplin who set her –and her voice– free. The 13-CD set chronicles the thrust of her career by re-releasing all of the recordings, remastered as necessary, that she made with Manfred Eichler's intrepid (and consummately professional) ECM over the 40 years since Monk's career broke.

No disrespect to Janis, as beloved an artist as rock has ever produced, but Monk took her newly freed voice to heights, depths, and expressive ranges arguably no other vocal artist has attempted or even dared. She has taken her singular work onstage in equally varied settings, underscoring the sheer courage of her artistry.

Extended Techniques

Even when her music entailed collaboration with similarly inclined colleagues (including filmmakers along with the best jazz musicians on the planet), there was no overlooking, say nothing of overhearing, the primacy of her work. A voice that whispered and unrepentantly shrieked (she credited Joplin in particular with proving definitively that a vocal sound did not have to be traditionally beautiful to carry, or last, or be beautiful), cooed and struck like lightning, carved out of space itself bodies of sound, and silences that speak.

Describing her technical accomplishment as the creation of extended vocal techniques, accurate as it is, seems an understatement, missing the point that "extended techniques" is a core value of genuinely questing artists, and that Monk's "extensions" were early and radical.

When her music is grouped with the work of others, prominent among them are other other-sexual artistic pioneers: Harry Partch, John Cage, and Cage's lifelong personal and artistic partner, choreographer Merce Cunningham. Singers before Monk pushed limits, including those of sexuality and its liberation, but none has created a more cosmic sense of what counts as femininity.

For Monk, studio work offered the same specific opportunities as they did for pianist Glenn Gould. For musicians of their inclinations and talents, recordings were not tamer, better groomed accounts of what was taken before the live public (though Monk cherished that audience segment far longer than Gould could manage) but performances in themselves. Monk's singular recordings are collected here with almost equally brilliant annotation. This is no "big box" released with fanfare but no documentation for holiday commercial consumption.

Artistic Evolution

Most such collections document an artist's development, and these recordings – released in their original form except for the inevitable digitization of the recording of later pieces – certainly do that. But what they also demonstrate is how arresting Monk's music-making was from the beginning, the development assured from the start.

Her detractors, notably few, may have dismissed her work as a musical Allen Ginsberg "Howl." But the two volumes of her earlier piano music offer a kind of history in Monk's words:

"One day in 1965, when I was at the piano vocalizing, I realized within a flash that within the voice there were limitless possibilities of color, texture, character, gender, resonance, ways of producing sound. From that time on, I began working with my own instrument, trying to discover the voices within."

What makes this collection essential even for listeners who already own some of the individual recordings is Monk's own, personal, probing essay, "The Soul's Messenger."

Monk is at the piano – self-accompanying is either precisely the right or exactly the wrong term for what she does – in the earliest recording in the set, "Gotham Lullaby."

Today, themed albums have all but displaced the aria and encore collections that were the bread and butter of the classical-vocal recording scene. Monk led the charge into what annotator Frank J. Oteri rightly calls "fixed media documentation of material she originally created for live performance." Monk wanted each album to be a self-contained listening experience.

It's an irony specific to this collection that it includes only one CD with piano music, Monk's beginnings. But it is Ursula Oppens (as important an exponent of "new music" as Monk is as a composer/performer) and Bruce Brubaker who play on "Piano Songs" of 2014, which include most of her annotated music for piano or two pianos.

The Recordings

These recordings are examples of the importance of recording to music, to art of most kinds. A force of Monk's torque would have made her way somehow, but it's clear that ECM's participation from the near beginning has supported her in essential ways, only beginning with providing top recording technology. It's been a real partnership. The documentation included in the set is model.

First-time Monks listeners could do much worse than go directly to "Spider Web Anthem," solo and layered vocal numbers into which instruments insinuate themselves, all of it unshy about adding what is beauty of sound by any standards. It's easier to get on first hearing than the more daring, boundary-breaking "late" pieces (though she's still working on a new collaboration with ECM).

In all the pieces, you encounter sound with infrastructure, the work of a keen musical intelligence that took the trouble to make its own vocabulary and grammar, color spectrum, and beat, and then work with them tirelessly. Each work creates its own language, as fluid as it is structured. Only later does it occur to most listeners that there is a bare minimum of verbal text, virtually a Monk creed. It's jazz and it's not jazz.

Appreciation of this dense, complex music not only rewards but mostly requires repeated hearings, though its initial impact is indisputable. It's not music that inclines you to have favorites. That said, I have a new admiration for "Volcano Songs" during our immediate moment in geological history, with major volcanoes erupting around the planet.

It's remarkable how comparable, if not similar, in reach and execution, her music is to experimental music's "other Monk," jazz giant Thelonius Monk, his creations for large ensembles as penetrating as his solo saxophone wail.

The More Familiar Human Voice

In other vocal music; if there is a piece of sure-fire, standard vocal music that's harrowingly difficult for both the singer and audience – deadly for the first and cathartic for the second – it is Francis Poulenc's "La Voix humaine" ("The Human Voice"), with a scorching text by surrealist Jean Cocteau. The piece has enjoyed a happy history in San Francisco, staged and otherwise. The latest contender on CD is French soprano Veronique Gens' with the Orchestre National de Lilles under Alexandre Bloch (Alpha).

Surprisingly few recordings of "La Voix" feature francophone sopranos, but, once heard, singers working in their native languages inevitably prevail. Suffice it to say here that Gens, one of the most highly regarded classical singers today, is in her element, in full command of the text not just aurally but dramatically. It's tough, gorgeous, wrenching stuff. The recording captures Gens at her vocal and artistic peak, having said which I'll quiet my own.

'Meredith Monk: The Recordings,' ECM New Series, 13-CD box, $124.98, and digital.

www.ecmrecords.com

Veronique Gens: Francis Poulenc, 'La Voix humaine,' Alpha Classics

www.outhere-music.com

Help keep the Bay Area Reporter going in these tough times. To support local, independent, LGBTQ journalism, consider becoming a BAR member.